In the summer of 1936, a Chinese artist made a visit to the Lake District and recorded what he found there in prose, poetry and painting. Chiang Yee was an academic who, at the time of his visit to the Lakes, taught Chinese at the School of Oriental Studies, University of London. He had come to London in 1933 and studied for an MSc in Economics at the London School of Economics.

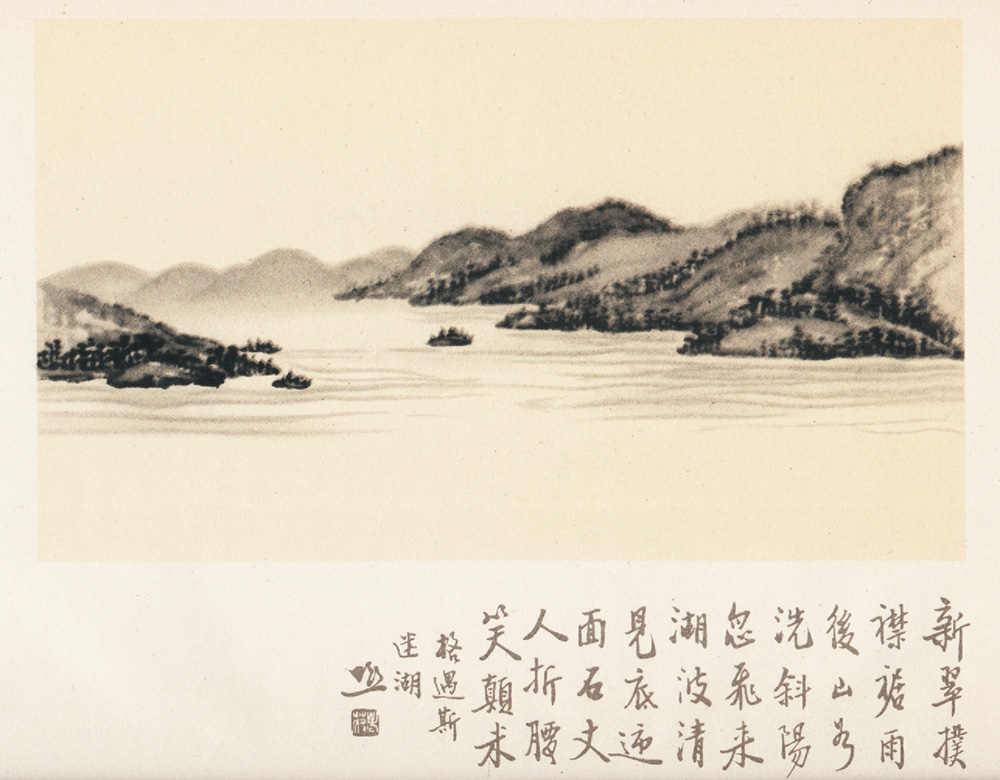

His Lakeland journal was published by Country Life in 1937, entitled, The Silent Traveller, A Chinese Artist in Lakeland. It’s a short book, running to just 67 pages, but it is rather wonderful and contains twelve plates depicting Lakeland scenes painted in the Chinese style and a preface by Herbert Read. The book was reprinted a number of times; my own copy is the 1944 reprint, which sold for eight shillings and sixpence (equivalent to about £13.30 today).

This imprint of the book was printed to the “War Economy Standard”. During the Second World War, paper was rationed and the supply of paper to publishers was reduced to 60% of what they had previously used. Publishers also agreed to abide by strict guidelines set by the Ministry of Supply which dictated print size, number of words per page and the use of blank pages in an effort to use paper more efficiently.

Despite its age, the book is in remarkably good condition. Inevitably, the paper has yellowed but there is very little foxing and the original paper jacket is largely intact.

Chiang Yee went on to publish a series of “Silent Traveller” books about visits to other locations in the UK and around the world, the last of which was The Silent Traveller in Japan, published in 1972. He died at home in China in 1977.

The Lakeland book is fascinating, not only because it is the first of The Silent Traveller books, but mostly because it depicts a social scene, modes of transport and other historical anachronisms that have changed beyond recognition, set against a landscape that has barely changed at all. This historical dissonance is mediated through the senses of someone to whom both English society and Cumbrian landscape are completely alien. The result is amusing and highly informative.

The book begins with Chiang arriving at the tiny railway station of Seascale at eight o’clock in the evening of 31st July, 1936 and his attempt to reach his lodgings at Wasdale Head, thirteen miles away.

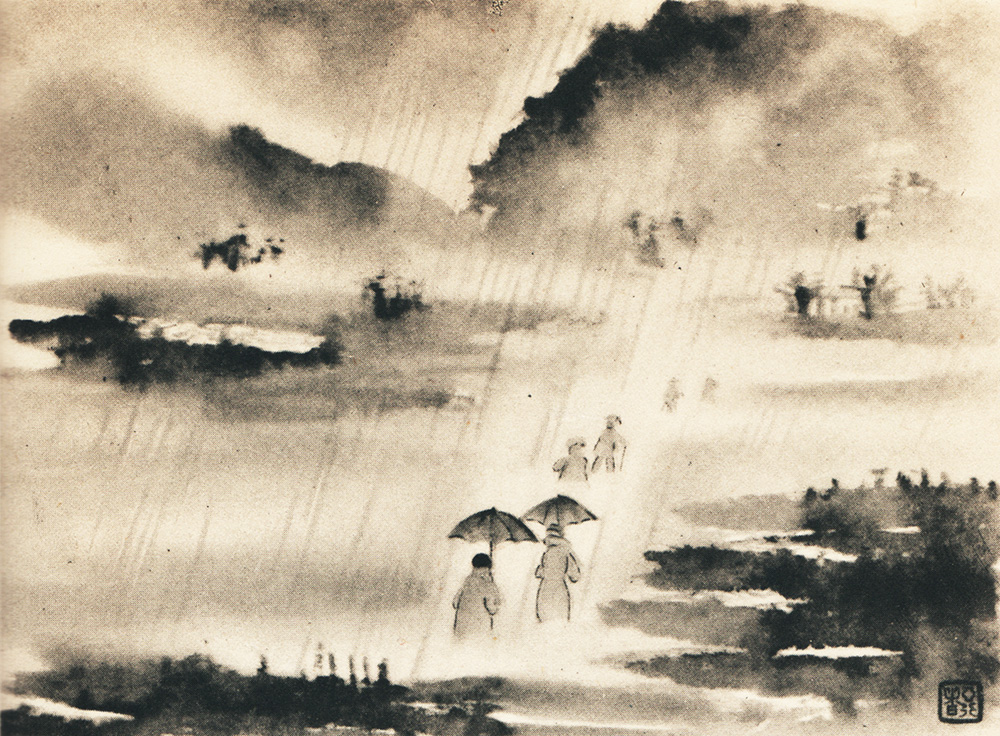

“I was expecting to be met by someone from the lodgings, for I had made arrangements with the landlady beforehand. The wind grew fiercer and fiercer and the rain fell in torrents.”

And so begins a typically wet summer visit to the Lake District.

Chiang eventually reaches the farmhouse at Wasdale Head where he has arranged to stay and experiences a familiar English welcome.

“On arriving at my destination, the landlady seemed not to have expected me to-day; though the welcome was not warm I was attracted by the appearance of her small farmhouse, totally different from the Chinese ones…”

At no point in the book does Chiang mention or even allude to racism but for the contemporary reader, it’s hard not to wonder whether that was what he experienced.

Of course, he visits the Lake District to experience the mountains and not the people. The book is full of comparisons between the landscape he knows from home in China and that of the Cumbrian Fells. Mostly, he is beguiled by what he finds and spends the first few days of his trip around Wasdale and the shores of Wastwater.

Chiang is bemused by the outdoor clothing of other visitors and appears to be totally unprepared for the weather and the terrain. At one point he has to turn back one third of the way up “Scawfell”. Describing his companion on that walk, he says:

“He was fully equipped for climbing, but I looked like nothing else but a London sightseer, with a small camera in my hand…

…Before we had gone far we found ourselves impeded by streams, and every place was terribly wet. My companion was worried about my thin shoes and socks, but though these were soaked through already, I really did not care at all.”

The book is written in the form of a journal with a chapter for each leg of the visit. I don’t think there is a single chapter in which Chiang does not get soaked to the skin but he takes it all in his stride. I can only guess that in the days before modern waterproof fabrics, people were just used to getting very wet in poor weather.

“Then it began to rain… I walked on and on in the rain, smiling and making friends with the particles of mist as they touched my face. Although I had no umbrella or mackintosh with me, the custom of nearly every English inhabitant, but one to which I was not yet used, I hardly noticed that my clothes were quickly becoming soaked through; I was happy in the rain and preferred the misty mountains and trees.”

On the 3rd August, our intrepid author walks to Seatoller and then a bus to Keswick where he undertakes a walk around Derwentwater. He hasn’t booked any accommodation, he just goes there, assuming that he’ll find something. All through the book, this unassuming man moves from one place to another in a beautiful naivety that never gets him into serious trouble. Along the way, he marvels and wonders at the landscape, painting scenes, writing poetry and describing his journey in lovely prose.

“I took a rest on a seat, perched on a high cliff by the lake side and saw distant Skiddaw as if she were a noble lady of Elizabethan times sitting there with her robes and draperies widely spread around her of purplish and brown colour, and shining in the reflection of the setting sun.”

During his stay at Keswick, Chiang joins a bus tour of the surrounding country, hoping to see more of the district than is possible on foot.

“The motor tour started at 10.30, and there were seven of us in the party. It was a disappointing excursion — I knew it would be so beforehand — for the car drove too fast and the driver was a man without taste, shouting the names of lakes and mountains, pointing out the properties of famous noblemen, etc., without giving us any opportunity of enjoying the actual scenery.”

That passage could easily have been written by Alfred Wainwright, whose disdain for people and love of landscape would have caused a similar reaction.

After Derwentwater, he moves on to Buttermere and Crummockwater, where he spends the only sunny day of his trip, and then to Windermere where he despairs of the crowds, likening it to Oxford Street in London, and finally to Rydal Water and Grasmere on the 11th August where he pays homage to William Wordsworth.

“What interested me most were the surroundings which stimulated the poet to compose his poems and convey his ingenious thoughts. I imagined his original environment at the time when he was composing must not be in the least like what we have before us — so many people coming and going, so many hotels and cars.”

It seems that not much has changed at Grasmere since 1936!

The book concludes with a comparison between the Lake District and that of his own mountain landscape in China. It’s clear that he misses his mountains and that this trip is an attempt to remind himself of home. Unfortunately, the Lake District comes a poor second in this comparison, the lakes and mountains being more diminutive than those in his home country.

“I hope my readers will not feel displeasure with this honest comment of mine; I am a Chinese, the native of a country rich in immense forms of mountain and water. I would grant power and lordliness to Scawfell Pike, but on the whole those mountains and lakes were charming miniatures by comparison with some of ours.”

Chiang Yee’s book is a curio, it’s certainly not the sort of book that would be picked up by a publisher today but it’s well worth a read if you have any interest in the Lake District and it provides an interesting insight into English society in 1936 as seen through the eyes of a foreigner. It’s a worthy addition to my Lake District library and will be filed alongside Alfred Wainwright, Mark Richards and Vivienne Crow.∗

For more information on Chiang Yee, see Anna Wu’s article, The silent traveller: Chiang Yee in Britain 1933-55 published in the V&A Online Journal.

Tagged: Lake District